For a couple of months, silence has been the soundtrack of our lives. In this phase in which we try to exorcise the lockdown amid a thousand uncertainties, the noises of the city started playing as background for our activities.

Today we let Endo Sensei guide us in our reflection. Not Seishiro, but Shusaku, who was an illustrious Japanese writer of the twentieth century.

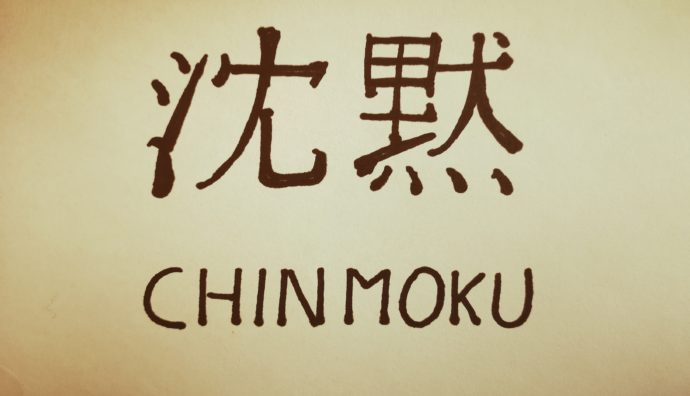

沈 黙, Chinmoku – Silence, is a novel written in 1966, based on historical research on the painful chapter in the Japanese history of the persecution of Christianity in feudal Japan in the 1600s and the subsequent suppression of the cult obtained with extreme violence.

We schedule for forthcoming posts a reflection that we deem necessary to try to analyze the perspective of all Endo’s literary activity, that is, to conceive Christianity as the point of contact between the West and the East. We are Western Martial Arts practitioners: whatever our experience may be, we are imbued with values that derive from the environment in which we were born and in which we live. At the same time, we perceive the echo of a value system conveyed by martial practice. We believe that it is an essential starting point, that of a Japanese Christian to understand each other more and more. As Western people, as Christians (for those who are), as practitioners. As said, we will be back soon on that.

The novel is still available in its translation and is a reading that we strongly recommend. We therefore do not intend to reveal its content or its ending.

Let’s focus on a theme that has traversed generations. On a theme that today, in full global crisis due to the effect of an invisible virus, resounds in many hearts. The silence of God. The difficulty, the impossibility, the challenge of seeking meaning in the face of human suffering.

We repeat: it is a book that deserves reading, also to demythologize a little the aura of harmony and perfection that sometimes hovers in our fantasies thinking about the epic of the samurai. The main character, facing with the barbaric killing of a guy who refuses to deny his faith exclaims:

So, Lord, why are you silent? You should know, that half-blind farmer died here for you. Yet this stupid tranquility continues, this imperturbability continues at midday.

Only the hum of a fly. And you, as if this stupid and atrocious fact didn’t matter to you, why are looking away?

How many times, we physically kept ourselves silent with the mokuso practice, at the Dojo, actualy not sticking to that silence of the mind that brings out the dimension of truth. In a way it was just a mechanical habit.

How many times have we defended our stupid tranquility, reacting or not acting to what life has placed before us? Waiting to find scapegoats outside of us for our sloth, our fear, our limits, our betrayals?

How many times, in fact, have we been merciless instigators and executors of God’s silence?

These months have brought silence back to the center. A silence that can reveal absence or presence; which can herald dawn or accompany the last rays of light in the darkness.

Silence is probably the keystone of our entire existence, in all its aspects. At home, at work, at the Dojo. It is up to us to understand it, accepting its not always comfortable language.

Lord, I resented your silence, says the main character. Endo makes Christ answer: “I was not silent. I suffered beside you.”

There is a form of communication, between teacher and student, which is defined “from heart to heart -i shin den shin” and is a non-verbal form, because words, even the most beautiful, the most sought after, have a limit, which only the heart can help to go beyond. Not the physical condition, nor the mind, nor the senses.

The hope is that the voids, the distances, the tears that this situation has brought and will continue to bring, can be filled with a silence that speaks, because it is inhabited by a relationship.