One of the advantages of practicing Aikido is that our training is a unique blending of free hand and weapon techniques.

Since it would be not so wise to let housewives, fatty clerks, students and retired people to wave sharp katanas and knoves, usually we use wooden replicas of swords and knives. The jo, the long stick that once held a spear is naturally made of wood and somehow from childhood we are used to hit something ore someone with sticks and clubs and this makes jo practice more familiar.

Anyway, the point is that when we train sword techniques, we work on the development of accuracy and decision making skill.

It doesn’t matter wheter or not we are training in the Morihiro Saito’s Aikiken method ore if we rely on other styles and schools (i.e. Kashima or Katori Shinto Ryu). Of course we could start long discussions about the coherence of weapon techinques and tai jutsu techniques, being the Saito’s didactic methodolgy more integrated and linked through all the steps (tai jutsu, buki waza), but this would lead to such a stream of comments that Internet, the whole Internet could have some brownouts.

Every strike we perform with a sword, improves our capabilities. Grounding, extension, accuracy, control, relaxation, distance, inclination, speed…

Both in a physical and metaphoric perspective, we perform a sequence of acts of division. A sort of “pruning” of technical and mental impurities.

While a grab and in most of cases a fist and a strike (even with the jo) may result in reversible pain -as oure bruises witness after some classes- cutting defines a “before” and an “after”, referring to a situation that won’t ever be the same. Any more.

If you are lucky and your sensei has a certain level of sword mastery, you’d probably are familiar with terms with “ukeru ken, kimeru ken, satsujinken and katsujinken”.

Trying to “zip” centuries of Japanese culture and spirituality, we could state that in the old times the sword was a very common tool. Useful both to make a path through bushes and to protect. Or to prevail on somebody else. Or all those things mixed up.

Therefore there was a way of using the sword in a fashion it could “give death” (satsujinken) or, at the opposite, in a way it could serve to protect and defend, giving therefore “life” (katsujinken). One of the most famous Japanese storyis the story of sword smiths, Masamune and Muramasa and it is all rooted on those two concepts.

In this framework, it is easy to understand why the practice of the sword is all the time tied to the dualistic concepts of “ukeru ken”, the sword that absorbs an attack and “kimeru ken”, the sword that puts a definitive “kime”, the final intention in an action.

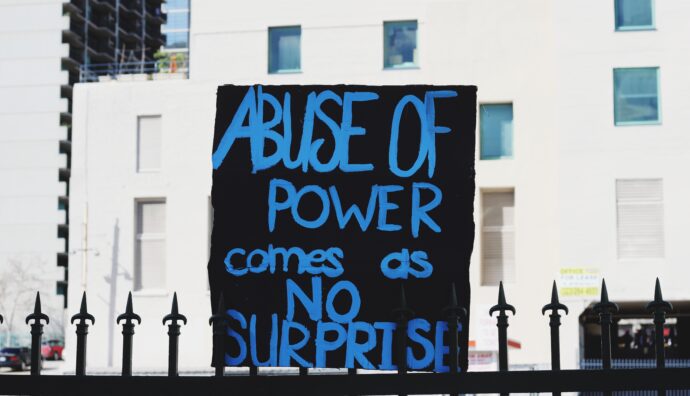

A superficial and naive approach to ken training and the partial and polarized knowledge of the historical and cultural premises, may lead to some dangerous misunderstanding.

Seeing the sword as a tool that can restore the order from the chaos is not neither good nor bad. In effect, all the Japanese theogony starts from a coral blade that originates the Japanese islands from the original chaos.

Yet, the sword had -and as archetype, still has- a strong valence of a militar tool for ensuring order in a society. A kind of order that is granted through the repression of everything that is not allowed by the ones who hold the sword.

Thinking we are practicing Aikido in such a state we are able to freely switch from satsujinken to katsujinken, may be the ultimate target of our technical evoultionary process. But, for sure, it is not what O’ Sensei stated in “The Art of Peace” when he wrote “Even though our path is completely different from the warrior arts of the past, it is not necessary to abandon totally the old ways. Absorb venerable traditions into this new art by clothing them with fresh garments, and build on the classic styles to create better forms”

Moreover thinking to be able to manage every situation (on the tatami, outside the dojo) with a perfect calm, is not real.

Simply: it is not the way we are equipped on this Earth. There will be always a border that will define our comfort zone. And against that border barbarian thoughts and events will try to seize us.

Yet, sometimes, everyone of us, especially while waving a ken, feels an higher sense of power. Our system is not used to make many decisions on purpose. We must train and cleanse our decision making.

The mere repeating of strikes, without a coherent inner work on the intention we put while striking, may lead us into the temptation of feeleing ourselves as almighty.

Which is childish. And the death of Aikido purpose, which is ensuring us an ongoing training, based on the admission that our develompment is not fulfilled. Not yet.

Tasting the capability to give death or to preserve it is good. We do have power and related responsibility.

Practicing ken is very good: our daily life needs to experience the definitivity, the idea that something done in the past echoes in the present and in future. With good waves or bad impacts.

A failure will be assessed as a failure, as well a success. A betrayal won’t change its name. A healed relationship won’t be always looking at its unpleasant past.

In this case, practice helps life to bring life.

If we are stuck in seeing ourselves like perfect warriors, a kind of robot with perfect techniques and no understanding of the meaning of what we are studying, we miss a lot of good opportunities to grow and we create a distorted image of us and of what we pretend to live, in perfect samurai clothes.

Disclaimer Photo by Samantha Sophia on Unsplash